Tony

De Franco's long love of the mechanical led to more than a job

Monday, July 31,

2006

You walk into De Franco's Lock & Safe on McBride Avenue in Paterson and this is what you see: Tony, white-haired and personable, standing behind the counter; a lot of keys and key paraphernalia; a lot of locks and lock paraphernalia; and Amendment II of the Bill of Rights, asserting the people's right to keep and bear arms.

Then there are the raffle tickets, the photographs of eagles, the wall box gun shop that Tony retrofitted with little overhead lights, the machine that cuts keys, the key cutting price list, gumball dispensers, a National Rifle Association medallion, a "scissors sharpened while U wait" sign and a purported Hitler quote in favor of gun control (several Web sites debunk the quote).

De Franco's Lock & Safe may be a key and lock store in business for 36 years, but Tony is about much more than enabling customers to get into their cars or keep others out of their homes.

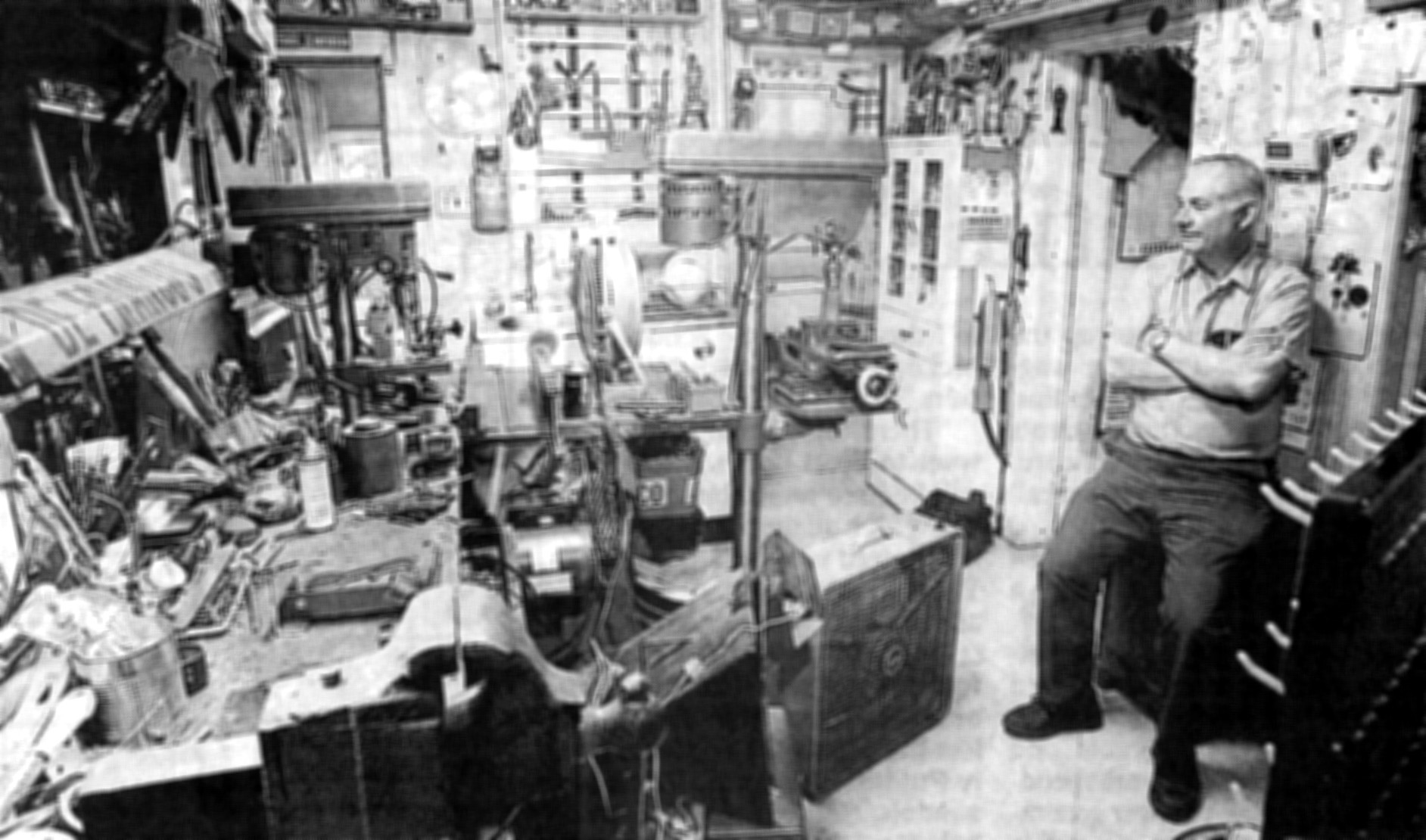

And you will

learn this should you be invited into the back of the store, where

you'll see how this locksmith occupies his time when he's not fixing

locks. Tony is not shy about expressing his thoughts or sharing his

interests.

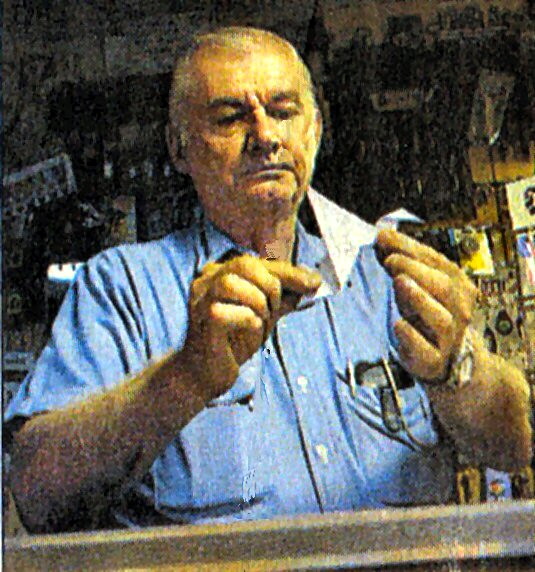

But first you should understand this about Tony: he was always mechanically minded. As a kid he took things apart to see how they worked and then put them back together. He likes precision. He likes things to operate correctly. He makes sure he cuts a key to fit its lock exactly, unlike other, big-store places, he says, that cut keys imprecisely, making a person jiggle the metal around in the lock until it clicks.

"If you want the job done right you have to do it yourself," he says, by way of explaining why he does not have an employee.

His mechanical ability extends to anything, he says. And he can repair anything, he says. "Pick something," he dares.

He fixes clocks, he welds handles back on pasta colanders for his older customers, he repairs eyeglasses, he sharpens knives, lawnmower blades and scissors.

"Everybody's pushing computer buttons these days. No one knows how to do things," he complains.

In the postage-stamp backyard -- Tony lives over the store -- he grows apples, peaches, pears, plums, eggplant, basil and peppers. He's trying a different way to grow tomatoes, by hanging them upside down.

In the bathroom he displays several fish he carved out of wood and a painting of animals he did on an old Red Lobster linen napkin.

Right now on his workbench lies a metal target for a friend's son's gun target practice. The target is shaped like a squirrel.

The back room -- well, all three back rooms -- are a well-ordered jumble. Every bit of space is taken up with keys, equipment, wrenches, snow shoes, key chains he makes himself, sculptures he made himself, a self-portrait carved from wood, a work bench, a drill press, telephone numbers written in pencil on the wall above the telephone, stickers that say things like: "Sure you can have my gun ... Bullets first," and "Diplomacy: the art of saying 'nice doggie' 'til you can find a rock," tanned animal hides, beaver fur and bottles of herbs, including burdock and devil's claw.

"The doctors today

don't want to cure you. They want to treat you," he says, "so they can

pay for their summer houses all over the place."

"The doctors today

don't want to cure you. They want to treat you," he says, "so they can

pay for their summer houses all over the place."

The locksmith is not only a hunter but also a trapper, and in a glass-fronted display case sit rows of skulls of animals he shot or trapped – beavers, otters, mink, raccoons and deer. He used to make little baby beaver Christmas tree ornaments from the beavers.

In the same room he stores a knife whose cross-hatched handle is made from the right leg bone of an 8-point, 144-pound buck he shot in 1996. He also made the sheath. Tanned the leather himself, stitched it up. Tony learned tanning from his grandfather, who owned Rocco De Franco Shoe Repair on Main Avenue.

The kid who took things apart to learn how they worked is now the 62-year-old man who makes sculptures out of machine parts and tools. In that room with the herbs and the animal skulls, he displays a stork he made from a drift pin, bent connecting rods, two valves and two transmission gears, and an elephant -- made from two end caps and reducing fitting with a pipe extension -- squashing a white Uncle Sam, who is lying on a red and black United States. The elephant represents the U.S. government walking all over white people, Tony said. The red and black on the outline of the U.S. represents "camouflage communism."

Tony keeps hidden what he calls the "erotic art" he makes, so as not to offend anybody, he says.

Way up on a shelf near the refrigerator is a carved alien made of wood, carved, Tony says, before "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" came out in 1977. Tony's alien has no eyes though, because in Tony's world the pollution has gotten so bad the aliens can't use them. Tony's aliens see everything telepathically.

Yup, the world is in a terrible mess, he says. "We're ready for the big flush. It's not a pessimistic outlook, it's just reality."

Tony is a man who never gets bored. "How could you get bored?" he asks. "People get bored and they don't know what to do. Man, get a life. There's a spider I was going to make ..." And he pulls out a metal end cap he'll use for the body of a black widow spider and a couple of the decapitated lag bolts he'll use for the legs.

But Tony's

art does not always stray from his craft. He made a brass padlock shaped

like a violin. It is an intricate, lovely piece of work, maybe a foot high. The

violin strings lift, the section with the bridge turns and the keyhole

is revealed. He made the filigreed key, too.

lovely piece of work, maybe a foot high. The

violin strings lift, the section with the bridge turns and the keyhole

is revealed. He made the filigreed key, too.

And he still finds locksmithing interesting. You constantly come across new things, he says, especially with safes -- electronics and biometrics for example.

The little two-family house on McBride Avenue, the house in which Tony and his wife have lived since 1970, is a modest place. Tucked into the cityscape, barely noticeable, it's as easy as pie to drive by. But the first floor, at least, is chock full of projects, very specific world views, locksmith equipment and, of course, Tony.