An Introduction to the History

of Locks

Locks

and keys were known long before the birth of Christ. They are mentioned

frequently in the Old Testament and in mythology. In the Book of Nehemiah,

chapter 3, it is stated that when repairing the old gates of the City of

Jerusalem - probably in 445 B.C. - they "set up the doors thereof, and the

locks thereof, and the bars thereof." At this time, locks were made of

wood. They were large and crude in design; yet their principle of operation was

the forerunner of the modern pin-tumbler locks of today.

Locks

and keys were known long before the birth of Christ. They are mentioned

frequently in the Old Testament and in mythology. In the Book of Nehemiah,

chapter 3, it is stated that when repairing the old gates of the City of

Jerusalem - probably in 445 B.C. - they "set up the doors thereof, and the

locks thereof, and the bars thereof." At this time, locks were made of

wood. They were large and crude in design; yet their principle of operation was

the forerunner of the modern pin-tumbler locks of today.

As locksmiths and metal workers became proficient in their craft, they were

invited to make locks and keys for the Royal Courts and for the churches and

cathedrals of Europe. They excelled in elaborate and high and highly detailed

ornamentation - often adapted to the religious theme.

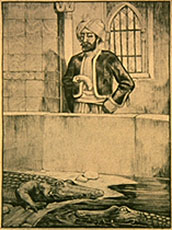

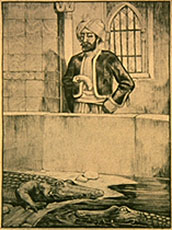

Security was a Guardian Angel

In India, in the days of the Emperor of Annam,

valuables were sealed into large blocks of wood, which were placed on small

islands or submerged into surrounding pools of the inner courts of the palace.

Here, they were protected by the royal "guardian angels," a number of

crocodiles kept on starvation rations so they were always hungry. To venture

into the water meant certain death for the intruder. The legitimate approach to

the treasure was to drug or kill the crocodiles.

Security was a Knotted Rope

For many hundreds of years, cords of ropes made of rush and fiber were used

to "lock" doors and tie up walls. The legend goes, a knotted rope

became a famous symbol of security. Intricately tied by Gordius, King of Phrygia,

and known by his name, the Gordian Knot, secured the yoke to the shaft of his

chariot. Its untying was pronounced by oracles to be possible only by the man

destined to conquer Asia. However, when Alexander the Great failed to undo the

Gordian Knot, he cut it swiftly with his sword, giving us the expression,

"to cut the Gordian Knot," meaning a bold, decisive action, effective

when milder measures fail.

Locks

from the Orient

Locks

from the Orient

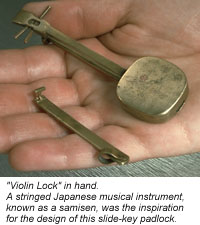

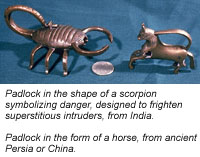

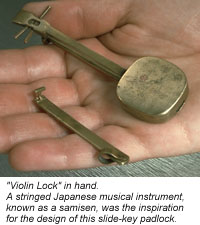

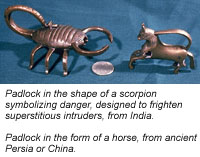

Brass and iron padlocks found in Europe and the Far East were popularized by

the Romans and the Chinese. They were particularly favored because they were

portable. They operated by keys that turned, screwed, and pushed. The push-key

padlock was of simple construction, the bolt kept in locked position by the

projection of a spring or springs. To unlock, the springs were compressed or

flattened by the key, which freed the bolt and permitted it to slide back.

Padlocks of this type are most universally used in the Orient today. The

decoration reflects the arts of the countries, and shapes often took the form of

animals - dragons, horses, dogs, even elephants and hippopotamuses. Padlocks

were often presented in pairs as gifts, with congratulatory messages in

cuneiform characters.

"Firsts" in

Development of Locks

The

first mechanical locks, made of wood, were probably created by a number of

civilizations at the same time. Records show them in use some 4,000 years ago in

Egypt. Fastened vertically on the door post, the wooden lock contained moveable

pins or "pin tumblers," that dropped by gravity into openings in the

cross piece or "bolt," and locked the door. It was operated by a

wooden key with pegs or prongs that raised the number of tumblers sufficiently

to clear the bolt so that it could be pulled back. This method of locking was

the forerunner of modern pin tumbler locks.

The

first mechanical locks, made of wood, were probably created by a number of

civilizations at the same time. Records show them in use some 4,000 years ago in

Egypt. Fastened vertically on the door post, the wooden lock contained moveable

pins or "pin tumblers," that dropped by gravity into openings in the

cross piece or "bolt," and locked the door. It was operated by a

wooden key with pegs or prongs that raised the number of tumblers sufficiently

to clear the bolt so that it could be pulled back. This method of locking was

the forerunner of modern pin tumbler locks.

The first all-metal lock appeared between the years 870 and 900, and are

attributed to the English craftsmen. They were simple bolts, made of iron with

wards (obstructions) fitted around the keyholes to prevent tampering.

The first use of wards (fixed projections in a lock) was introduced by the

Romans who devised obstructions to "ward off" the entry or turning of

the wrong key. Wards were notched and cut into decorative designs, and warding

became a basic locking mechanism for more than a thousand years. The first

padlocks were "convenient" locks as they could be carried and used

where necessary. They were known in early times to merchants traveling ancient

trade routes to Asia and Europe.

New concepts for locking devices were developed in Europe in the 17th century.

Early Bramah locks utilized a series of sliders in a circular pattern to provide

exceptional security. Bramah is the oldest lock company in the world and is

continuing to manufacture its famous mechanism 200 years later.

Primitives

The

first wooden lock was discovered in Persia as Khorsabad in security gate in the

palace of Sargon II, who reigned from 722 to 705 B.C. In appearance and

operation, it was very similar to this wooden cane-tumbler locks. The pegs at

the bit end of the key correspond to the bars, or the tumblers, in the bolt.

When inserted, the pegs lifted the tumblers so that the bolt could be retracted

and the door or gate could opened.

The

first wooden lock was discovered in Persia as Khorsabad in security gate in the

palace of Sargon II, who reigned from 722 to 705 B.C. In appearance and

operation, it was very similar to this wooden cane-tumbler locks. The pegs at

the bit end of the key correspond to the bars, or the tumblers, in the bolt.

When inserted, the pegs lifted the tumblers so that the bolt could be retracted

and the door or gate could opened.

Locks from the Old World

Designs of locks and keys were notably influenced by gothic architecture with

evermore elaborate ornamentation continuing into the period of the Renaissance.

Master locksmiths were invited to make locks for noblemen throughout Europe.

Because of this practice, it is difficult to document an antique lock as having

been produced specifically in the country where it was in use centuries ago.

German Castle Locks

The

period from the 14th through the 17th century was one of artistic accomplishment

by superb craftsmen. Locksmiths were skilled metalworkers who were becoming

internationally famous. They were invited to construct special locks for

noblemen throughout Europe. Using designs of coats-of-arms and symbolic shapes,

they devised intricate wards and bits for locks and keys and were inspired to

produce increasingly ornamental locks to harmonize with the architecture of

their clients' estates or castles. However, there were few improvements in

locking mechanisms. Security depended upon intricacies such as hidden keyholes,

trick devices, and complicated warding.

The

period from the 14th through the 17th century was one of artistic accomplishment

by superb craftsmen. Locksmiths were skilled metalworkers who were becoming

internationally famous. They were invited to construct special locks for

noblemen throughout Europe. Using designs of coats-of-arms and symbolic shapes,

they devised intricate wards and bits for locks and keys and were inspired to

produce increasingly ornamental locks to harmonize with the architecture of

their clients' estates or castles. However, there were few improvements in

locking mechanisms. Security depended upon intricacies such as hidden keyholes,

trick devices, and complicated warding.

Security in the 14th and 15th

Centuries

There

was little significant improvement in locking mechanisms in the 14th and 15th

centuries. However, ornamentation became increasingly elaborate. Craftsmen

excelled in metal work and designed and produced locks for gates, doors, chests,

and cupboards. A "Masterpiece" lock was never used on a door. It was

designed and produced as a one-of-a-kind by a journeyman locksmith, or iron

monger as a "test" to qualify him as a Master. Masterpiece locks were

often displayed without covers to show the component parts of the mechanisms,

their functions, the decorative designs of lockcases, and method of assembly.

There

was little significant improvement in locking mechanisms in the 14th and 15th

centuries. However, ornamentation became increasingly elaborate. Craftsmen

excelled in metal work and designed and produced locks for gates, doors, chests,

and cupboards. A "Masterpiece" lock was never used on a door. It was

designed and produced as a one-of-a-kind by a journeyman locksmith, or iron

monger as a "test" to qualify him as a Master. Masterpiece locks were

often displayed without covers to show the component parts of the mechanisms,

their functions, the decorative designs of lockcases, and method of assembly.

Padlocks

Padlocks

were known early in time to the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and other cultures of

the Near East, including the Chinese. It was believed that the padlock was first

used as a "travel" lock to protect merchandise from brigands along

ancient trade routes and seaboards and waterways where commerce was centered.

Made in small sizes to those of tremendous proportions, they represented various

geometric shapes, religious symbols, animals, fish, birds, hearts. They were

operated by keys that turned, screwed, pushed, and pulled. For better

efficiency, letter locks, or combination padlocks, were developed, which

eliminated keys and operated by alignment of letters or numbers on revolving

disks. Shown here is an American padlock dating back to the turn-of-the-century.

In the popular circular shape, this lock was probably used on a huge strongbox.

It has a single ward (obstruction) which the key bypasses to project the bolt.

Padlocks

were known early in time to the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and other cultures of

the Near East, including the Chinese. It was believed that the padlock was first

used as a "travel" lock to protect merchandise from brigands along

ancient trade routes and seaboards and waterways where commerce was centered.

Made in small sizes to those of tremendous proportions, they represented various

geometric shapes, religious symbols, animals, fish, birds, hearts. They were

operated by keys that turned, screwed, pushed, and pulled. For better

efficiency, letter locks, or combination padlocks, were developed, which

eliminated keys and operated by alignment of letters or numbers on revolving

disks. Shown here is an American padlock dating back to the turn-of-the-century.

In the popular circular shape, this lock was probably used on a huge strongbox.

It has a single ward (obstruction) which the key bypasses to project the bolt.

Locking In

Padlocks

were used throughout the centuries to lock prisoners and possessions. They were

usually made of iron, bronze, or brass, and were rugged in construction.

However, internal locking mechanisms were often fairly simple and easy to

defuse.

Padlocks

were used throughout the centuries to lock prisoners and possessions. They were

usually made of iron, bronze, or brass, and were rugged in construction.

However, internal locking mechanisms were often fairly simple and easy to

defuse.

This massive Russian padlock shown here was meticulously hand-forged early in

the reign of the last Czar, Nicholas II (1895-1918). The large circular ring on

the top is the "handle" or bow of a threaded key which is rotated into

the keyhole to disengage the locking mechanism. When the shackle is in the

locking position, the key is removed, and the plug is inserted to give the

illusion that there is no keyhole. The threaded portion of the key is then

screwed into its protective cover.

Inventive Ingenuity

As lock-picking became an art in the 18th century, the inventor met the

challenge of the burglar with increasingly complicated locking mechanisms. Among

the new improvements were keys with changeable bits, "curtain

closed-out" around keyholes to prevent tampering, alarm bells combined with

the action of the bolt, and "puzzle" or ring padlocks, with this

principle developing into dial face and bank vault locks, operating without keys

and known as combination locks.

The early puzzle padlocks were Oriental with from three to seven rings of

characters or letters which released the hasp when properly aligned. The dial

locks were similar in operation, and both types were combinated to unlock to

words or patterns of numbers known only to the owners or responsible persons.

At the left is the Eureka, a manipulation-proof combination lock with five

tumblers. For a faithful bank vault used at one time in the U.S. Treasury

Department. Patented in 1862 by Dodds, MacNeal, and Urban of Canton, Ohio. The

operating dial is a combination of letters and numbers and affords 1,073,741,824

combinations; to run through them all without interruption would take 2,042

years, 324 days, and 1 hour.

Castle and Chest Locks

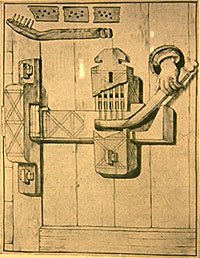

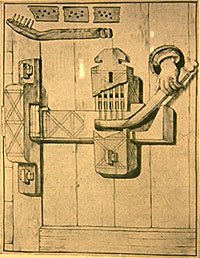

During

the gothic era, followed by the exuberant influence of the Renaissance, master

locksmiths were inspired to product the most intricate and the finest ornamental

locks of all time. This was the period when iron craftsmen and lock artisans

became internationally famous. They excelled in the forging, embossing,

engraving, chafing, and etching of metals, and were invited to make locks and

keys for the courts of Europe. Shown here is a spring latch lock for a castle

door. Its working mechanism is concealed in the classic dome, or ward house,

that shows the Moorish influence. Ornamented in the style of the period with

mythical figures and scrolls, it is particularly noteworthy as it illustrates

the coloring of metal, similar to the "niello" process. As the

craftsman lacked color, he created various stains for metal, which he used for

backgrounds to highlight his design.

During

the gothic era, followed by the exuberant influence of the Renaissance, master

locksmiths were inspired to product the most intricate and the finest ornamental

locks of all time. This was the period when iron craftsmen and lock artisans

became internationally famous. They excelled in the forging, embossing,

engraving, chafing, and etching of metals, and were invited to make locks and

keys for the courts of Europe. Shown here is a spring latch lock for a castle

door. Its working mechanism is concealed in the classic dome, or ward house,

that shows the Moorish influence. Ornamented in the style of the period with

mythical figures and scrolls, it is particularly noteworthy as it illustrates

the coloring of metal, similar to the "niello" process. As the

craftsman lacked color, he created various stains for metal, which he used for

backgrounds to highlight his design.

Locks for Treasure Chests

Locks for Treasure Chests

Since

the earliest times, chests were secured with strong and frequently very large

locks. They were used to protect precious metals, money, jewels, to store

clothing, and church vestments, archives and arms, linens and other household

articles, bridal finery, and even for burial of important people. Chest locks

were ornamented for household use, or were very plain and sturdy for chests that

were to be transported. Generally, they were mounted inside the chest, in a

vertical position, with bolts spreading to slide into the lid keeper.

The Key was a Latchstring

In pioneering days of Colonial America, the "key" to the lock of

the house often hung on the outside of the door. It was a length of string.

Doors were latched on the inside with a pivoted wooded bar or bolt, one end

dropping into a slot in the jamb. Attached was a piece of string that was

threaded through a small hole to the outside. To the visitor, the dangling

string was an immediate welcome, as pulling on it, raised the bolt and opened

the door. This lock and key became the origin of our expression of hospitality,

"the latch string is always out."

There were No Secrets in

Madrid

Several

centuries ago, in Spain, there was a great distrust of locks. To be safe, the

householders of a block hired a watchman to patrol the neighborhood and carry

the keys to their dwellings. To enter or leave a house, the resident clapped his

hands vigorously to summon the watchman with his key, so, all comings and goings

became a matter of public record and there was little chance for "hanky

panky" in old Madrid.

Several

centuries ago, in Spain, there was a great distrust of locks. To be safe, the

householders of a block hired a watchman to patrol the neighborhood and carry

the keys to their dwellings. To enter or leave a house, the resident clapped his

hands vigorously to summon the watchman with his key, so, all comings and goings

became a matter of public record and there was little chance for "hanky

panky" in old Madrid.

Marie Antoinette's Husband was

a Locksmith

His name was Louis, Louis XVI, King of France. Louis didn't particularly like

the business of being a king, but he had an extraordinary interest in mechanical

labor. He spent many happy hours in his house workshop forging metal and making

locks, skills taught to him by a locksmith named Gamin. He was particularly

proud of an iron security cabinet which we concealed in a wall to protect his

private papers. Unfortunately, Louis didn't reckon with the Revolutionists, as

his secret hiding place was revealed by Gamin, and his papers incriminated him.

History says, poor Louis, he was as good a locksmith as he was a bad king.

Safecracking Under Seas

As

a child, Charles Courtney was intrigued with everything mechanical that he could

fix or take apart. He was especially fascinated with locks, and so began his

lifelong career as a lock expert. However, he had resolved to become a diver and

do all the things his great, great uncle, Jules Verne, a novelist, had described

in his famous book, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea. Years later,

Charles Courtney realized his dream. Because of his talent for picking locks, he

was hired as a diver to open safes on sunken ships. He was the first to do a

locksmithing job 400 feet under water, and he recovered many millions of dollars

for the salvage companies. Charles Courtney achieved international fame as a

Master Locksmith, also known as a collector of antique locks, many of them now a

part of the Schlage collection.

The Safemakers and the Yeggs

Country banks, in the early 1800s were housed in crude buildings. Safes were

simple wooden shafts or strongboxes reinforced with sheet iron and secured with

padlocks. It was "easy money" for criminal to break in and smash the

safe, or carry it away for "cracking" in privacy. So began the race

between safemakers and safe breakers, or "yeggs" as they were called.

Manufacturers started to build solid iron safes with key-operated deadbolt

locks; yeggs soon defeated them by pouring explosives into the keyholes and

blowing the doors off their hinges. For better protection, lock makers developed

combination locks without keyholes, later combining them with tiny mechanism.

Vaults of steel and concrete were built into the structures of banks. Multiple

locking procedures were devised and so passed the era of the yegg.

To Please a Lady

Catherine

the Great, Czarina of Russia from 1762 to 1796, had one of the most notable lock

collections of her time. She admired the fine workmanship of artisans who

designed ornamental faceplates for locks and created padlocks in fanciful forms

to please a lady or a favored child. It is said that a famous Russian locksmith

gained his freedom from banishment to Siberia my making a chain for Catherine.

She was so impressed with his craftsmanship that she pardoned him. As the story

goes, this incident is credited with the origin of a saying that "it takes

89 keys to unlock a prison."

Catherine

the Great, Czarina of Russia from 1762 to 1796, had one of the most notable lock

collections of her time. She admired the fine workmanship of artisans who

designed ornamental faceplates for locks and created padlocks in fanciful forms

to please a lady or a favored child. It is said that a famous Russian locksmith

gained his freedom from banishment to Siberia my making a chain for Catherine.

She was so impressed with his craftsmanship that she pardoned him. As the story

goes, this incident is credited with the origin of a saying that "it takes

89 keys to unlock a prison."

Americana

In

the mid 1700s, locks were few in the Colonies and most were copies of European

mechanisms. With the founding of the Republic and the new prosperity, there was

a growing demand for sturdy door locks, padlocks, and locks for safes and

vaults, and so the American lock industry had its start. Each native craftsman

had his own ideas about security, and between 1774 and 1920, American lockmakers

patented some 3,000 varieties of lock devices. Among was the patent for a

"domestic lock," by Linus Yale, Sr. This lock was a modification of an

old Egyptian pin-tumbler principle that utilized a revolving cylinder.

In

the mid 1700s, locks were few in the Colonies and most were copies of European

mechanisms. With the founding of the Republic and the new prosperity, there was

a growing demand for sturdy door locks, padlocks, and locks for safes and

vaults, and so the American lock industry had its start. Each native craftsman

had his own ideas about security, and between 1774 and 1920, American lockmakers

patented some 3,000 varieties of lock devices. Among was the patent for a

"domestic lock," by Linus Yale, Sr. This lock was a modification of an

old Egyptian pin-tumbler principle that utilized a revolving cylinder.

In the early 1920s, Walter Schlage advanced the concept of a cylindrical

pin-tumbler lock by placing a push-button locking mechanism between the two

knobs. Emphasis was on security; yet equally important to the modern architect

and decorator, the lock became an intricate part of the door design. It was now

possible to select complimentary styles of locks, metals, and finishes. Shown

here is a rim lock from Fort Sumter at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The

Fort was the site of the start of the Civil War. On April 12, 1861, the

Confederate forces opened fire on Fort Sumter, a federal garrison. After a

bombardment of 36 hours, the Fort surrendered on April 14. The lock was found by

Captain James Kelly, formerly a blockade runner, when he was delivering

materials for the rebuilding of Fort Sumter at the close of the Civil War.

The revolutionary Schlage lock is a completely different concept of a

cylindrical lock with the button-in-the-knob mechanism placed between the knobs,

introduced by Walter Schlage in the early 1920s.

Elegance in Metal

During

the Middle Ages, locks and keys were highly ornate. Iron began to be worked

cold. It was no longer necessary for the smith to work quickly at the forge; he

now used a file, a cold chisel, and a saw with extraordinary dexterity. The

master locksmith designed special locks for cathedrals and churches in the shape

of a cross and embellished them with elaborate decorations. He acquired expert

skills in repoussť , ornametations, overlays, embossing, chaffing, piercing,

and created delicate fretwork in the popular scroll and leaf patterns of the

period.

During

the Middle Ages, locks and keys were highly ornate. Iron began to be worked

cold. It was no longer necessary for the smith to work quickly at the forge; he

now used a file, a cold chisel, and a saw with extraordinary dexterity. The

master locksmith designed special locks for cathedrals and churches in the shape

of a cross and embellished them with elaborate decorations. He acquired expert

skills in repoussť , ornametations, overlays, embossing, chaffing, piercing,

and created delicate fretwork in the popular scroll and leaf patterns of the

period.

Above is a Spanish chuck lock and key with hinged hasp and rim or lockplate with

pairs of facing animals. Belonging to Queen Isabella, this lock was probably

used to secure a storage chest that may have contained her royal robe and

personal fortune.

The Mystique of the Key

For

many centuries, keys represented authority, security, and power. Gods,

goddesses, and saints are described as holders of the keys to the Kingdom of

Heaven, to Bottomless Pit, to Gates of Earth and Sea. Kings, emperors, nobles of

the court, and cities and towns incorporated the symbol of the key into banners,

coats of arms and official seals. The delivery of keys to a castle, fortress, or

city was a ceremonial event, as is the presentation of the Key-To-The-City today

to a visiting dignitary.

For

many centuries, keys represented authority, security, and power. Gods,

goddesses, and saints are described as holders of the keys to the Kingdom of

Heaven, to Bottomless Pit, to Gates of Earth and Sea. Kings, emperors, nobles of

the court, and cities and towns incorporated the symbol of the key into banners,

coats of arms and official seals. The delivery of keys to a castle, fortress, or

city was a ceremonial event, as is the presentation of the Key-To-The-City today

to a visiting dignitary.

Shown here is a large Roman key.

Keys from the Time of Nero to

Queen Victoria

The key was a symbol of man's status, his authority. Many centuries ago in

Egypt, the importance of the "head of the household" was determined by

the number of keys he owned; they were large and were carried by slaves on their

shoulders. Should he have several slaves, or key bearers, he was considered to

be a man of great wealth and distinction. So, through the ages, the lock and its

key have become an intricate part of our culture. Locking up personal property,

the key symbolizes our desire for privacy and security for our possessions. This

emblem of keys from the early Roman period to the 19th century may include a

master key or two, but there are no duplicates.

The Ceremony of the Keys

If

you have visited the Tower of London, you will remember the warder, dressed in a

red tunic and wearing a Tudor hat and ruff. Familiarly, he is called a

Beefeater. Specifically, he is an Honorary Yeoman of the Guards, a member of the

Queen's bodyguard. If you spoke to him, you may have heard the story of the

Ceremony of the Keys. Every night, the Chief Warder locks the Tower gates and

brings the keys to headquarters in the ancient fortress. The sentry calls out

"Halt! Who comes there?" "The Keys." "Whose

keys?" "Queen Elizabeth's keys." Everyone presents arms

and the warder calls out, "God preserve Queen Elizabeth." The guard

responds, "Amen." Tonight and every night, this traditional ceremony

of Britain continues. The yeoman repeats the same words that have never been

changed in 450 years.

If

you have visited the Tower of London, you will remember the warder, dressed in a

red tunic and wearing a Tudor hat and ruff. Familiarly, he is called a

Beefeater. Specifically, he is an Honorary Yeoman of the Guards, a member of the

Queen's bodyguard. If you spoke to him, you may have heard the story of the

Ceremony of the Keys. Every night, the Chief Warder locks the Tower gates and

brings the keys to headquarters in the ancient fortress. The sentry calls out

"Halt! Who comes there?" "The Keys." "Whose

keys?" "Queen Elizabeth's keys." Everyone presents arms

and the warder calls out, "God preserve Queen Elizabeth." The guard

responds, "Amen." Tonight and every night, this traditional ceremony

of Britain continues. The yeoman repeats the same words that have never been

changed in 450 years.

Locks

and keys were known long before the birth of Christ. They are mentioned

frequently in the Old Testament and in mythology. In the Book of Nehemiah,

chapter 3, it is stated that when repairing the old gates of the City of

Jerusalem - probably in 445 B.C. - they "set up the doors thereof, and the

locks thereof, and the bars thereof." At this time, locks were made of

wood. They were large and crude in design; yet their principle of operation was

the forerunner of the modern pin-tumbler locks of today.

Locks

and keys were known long before the birth of Christ. They are mentioned

frequently in the Old Testament and in mythology. In the Book of Nehemiah,

chapter 3, it is stated that when repairing the old gates of the City of

Jerusalem - probably in 445 B.C. - they "set up the doors thereof, and the

locks thereof, and the bars thereof." At this time, locks were made of

wood. They were large and crude in design; yet their principle of operation was

the forerunner of the modern pin-tumbler locks of today.

Locks

from the Orient

Locks

from the Orient The

first mechanical locks, made of wood, were probably created by a number of

civilizations at the same time. Records show them in use some 4,000 years ago in

Egypt. Fastened vertically on the door post, the wooden lock contained moveable

pins or "pin tumblers," that dropped by gravity into openings in the

cross piece or "bolt," and locked the door. It was operated by a

wooden key with pegs or prongs that raised the number of tumblers sufficiently

to clear the bolt so that it could be pulled back. This method of locking was

the forerunner of modern pin tumbler locks.

The

first mechanical locks, made of wood, were probably created by a number of

civilizations at the same time. Records show them in use some 4,000 years ago in

Egypt. Fastened vertically on the door post, the wooden lock contained moveable

pins or "pin tumblers," that dropped by gravity into openings in the

cross piece or "bolt," and locked the door. It was operated by a

wooden key with pegs or prongs that raised the number of tumblers sufficiently

to clear the bolt so that it could be pulled back. This method of locking was

the forerunner of modern pin tumbler locks. The

first wooden lock was discovered in Persia as Khorsabad in security gate in the

palace of Sargon II, who reigned from 722 to 705 B.C. In appearance and

operation, it was very similar to this wooden cane-tumbler locks. The pegs at

the bit end of the key correspond to the bars, or the tumblers, in the bolt.

When inserted, the pegs lifted the tumblers so that the bolt could be retracted

and the door or gate could opened.

The

first wooden lock was discovered in Persia as Khorsabad in security gate in the

palace of Sargon II, who reigned from 722 to 705 B.C. In appearance and

operation, it was very similar to this wooden cane-tumbler locks. The pegs at

the bit end of the key correspond to the bars, or the tumblers, in the bolt.

When inserted, the pegs lifted the tumblers so that the bolt could be retracted

and the door or gate could opened.

The

period from the 14th through the 17th century was one of artistic accomplishment

by superb craftsmen. Locksmiths were skilled metalworkers who were becoming

internationally famous. They were invited to construct special locks for

noblemen throughout Europe. Using designs of coats-of-arms and symbolic shapes,

they devised intricate wards and bits for locks and keys and were inspired to

produce increasingly ornamental locks to harmonize with the architecture of

their clients' estates or castles. However, there were few improvements in

locking mechanisms. Security depended upon intricacies such as hidden keyholes,

trick devices, and complicated warding.

The

period from the 14th through the 17th century was one of artistic accomplishment

by superb craftsmen. Locksmiths were skilled metalworkers who were becoming

internationally famous. They were invited to construct special locks for

noblemen throughout Europe. Using designs of coats-of-arms and symbolic shapes,

they devised intricate wards and bits for locks and keys and were inspired to

produce increasingly ornamental locks to harmonize with the architecture of

their clients' estates or castles. However, there were few improvements in

locking mechanisms. Security depended upon intricacies such as hidden keyholes,

trick devices, and complicated warding. There

was little significant improvement in locking mechanisms in the 14th and 15th

centuries. However, ornamentation became increasingly elaborate. Craftsmen

excelled in metal work and designed and produced locks for gates, doors, chests,

and cupboards. A "Masterpiece" lock was never used on a door. It was

designed and produced as a one-of-a-kind by a journeyman locksmith, or iron

monger as a "test" to qualify him as a Master. Masterpiece locks were

often displayed without covers to show the component parts of the mechanisms,

their functions, the decorative designs of lockcases, and method of assembly.

There

was little significant improvement in locking mechanisms in the 14th and 15th

centuries. However, ornamentation became increasingly elaborate. Craftsmen

excelled in metal work and designed and produced locks for gates, doors, chests,

and cupboards. A "Masterpiece" lock was never used on a door. It was

designed and produced as a one-of-a-kind by a journeyman locksmith, or iron

monger as a "test" to qualify him as a Master. Masterpiece locks were

often displayed without covers to show the component parts of the mechanisms,

their functions, the decorative designs of lockcases, and method of assembly. Padlocks

were known early in time to the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and other cultures of

the Near East, including the Chinese. It was believed that the padlock was first

used as a "travel" lock to protect merchandise from brigands along

ancient trade routes and seaboards and waterways where commerce was centered.

Made in small sizes to those of tremendous proportions, they represented various

geometric shapes, religious symbols, animals, fish, birds, hearts. They were

operated by keys that turned, screwed, pushed, and pulled. For better

efficiency, letter locks, or combination padlocks, were developed, which

eliminated keys and operated by alignment of letters or numbers on revolving

disks. Shown here is an American padlock dating back to the turn-of-the-century.

In the popular circular shape, this lock was probably used on a huge strongbox.

It has a single ward (obstruction) which the key bypasses to project the bolt.

Padlocks

were known early in time to the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and other cultures of

the Near East, including the Chinese. It was believed that the padlock was first

used as a "travel" lock to protect merchandise from brigands along

ancient trade routes and seaboards and waterways where commerce was centered.

Made in small sizes to those of tremendous proportions, they represented various

geometric shapes, religious symbols, animals, fish, birds, hearts. They were

operated by keys that turned, screwed, pushed, and pulled. For better

efficiency, letter locks, or combination padlocks, were developed, which

eliminated keys and operated by alignment of letters or numbers on revolving

disks. Shown here is an American padlock dating back to the turn-of-the-century.

In the popular circular shape, this lock was probably used on a huge strongbox.

It has a single ward (obstruction) which the key bypasses to project the bolt. Padlocks

were used throughout the centuries to lock prisoners and possessions. They were

usually made of iron, bronze, or brass, and were rugged in construction.

However, internal locking mechanisms were often fairly simple and easy to

defuse.

Padlocks

were used throughout the centuries to lock prisoners and possessions. They were

usually made of iron, bronze, or brass, and were rugged in construction.

However, internal locking mechanisms were often fairly simple and easy to

defuse.

During

the gothic era, followed by the exuberant influence of the Renaissance, master

locksmiths were inspired to product the most intricate and the finest ornamental

locks of all time. This was the period when iron craftsmen and lock artisans

became internationally famous. They excelled in the forging, embossing,

engraving, chafing, and etching of metals, and were invited to make locks and

keys for the courts of Europe. Shown here is a spring latch lock for a castle

door. Its working mechanism is concealed in the classic dome, or ward house,

that shows the Moorish influence. Ornamented in the style of the period with

mythical figures and scrolls, it is particularly noteworthy as it illustrates

the coloring of metal, similar to the "niello" process. As the

craftsman lacked color, he created various stains for metal, which he used for

backgrounds to highlight his design.

During

the gothic era, followed by the exuberant influence of the Renaissance, master

locksmiths were inspired to product the most intricate and the finest ornamental

locks of all time. This was the period when iron craftsmen and lock artisans

became internationally famous. They excelled in the forging, embossing,

engraving, chafing, and etching of metals, and were invited to make locks and

keys for the courts of Europe. Shown here is a spring latch lock for a castle

door. Its working mechanism is concealed in the classic dome, or ward house,

that shows the Moorish influence. Ornamented in the style of the period with

mythical figures and scrolls, it is particularly noteworthy as it illustrates

the coloring of metal, similar to the "niello" process. As the

craftsman lacked color, he created various stains for metal, which he used for

backgrounds to highlight his design. Locks for Treasure Chests

Locks for Treasure Chests

Several

centuries ago, in Spain, there was a great distrust of locks. To be safe, the

householders of a block hired a watchman to patrol the neighborhood and carry

the keys to their dwellings. To enter or leave a house, the resident clapped his

hands vigorously to summon the watchman with his key, so, all comings and goings

became a matter of public record and there was little chance for "hanky

panky" in old Madrid.

Several

centuries ago, in Spain, there was a great distrust of locks. To be safe, the

householders of a block hired a watchman to patrol the neighborhood and carry

the keys to their dwellings. To enter or leave a house, the resident clapped his

hands vigorously to summon the watchman with his key, so, all comings and goings

became a matter of public record and there was little chance for "hanky

panky" in old Madrid.

Catherine

the Great, Czarina of Russia from 1762 to 1796, had one of the most notable lock

collections of her time. She admired the fine workmanship of artisans who

designed ornamental faceplates for locks and created padlocks in fanciful forms

to please a lady or a favored child. It is said that a famous Russian locksmith

gained his freedom from banishment to Siberia my making a chain for Catherine.

She was so impressed with his craftsmanship that she pardoned him. As the story

goes, this incident is credited with the origin of a saying that "it takes

89 keys to unlock a prison."

Catherine

the Great, Czarina of Russia from 1762 to 1796, had one of the most notable lock

collections of her time. She admired the fine workmanship of artisans who

designed ornamental faceplates for locks and created padlocks in fanciful forms

to please a lady or a favored child. It is said that a famous Russian locksmith

gained his freedom from banishment to Siberia my making a chain for Catherine.

She was so impressed with his craftsmanship that she pardoned him. As the story

goes, this incident is credited with the origin of a saying that "it takes

89 keys to unlock a prison." In

the mid 1700s, locks were few in the Colonies and most were copies of European

mechanisms. With the founding of the Republic and the new prosperity, there was

a growing demand for sturdy door locks, padlocks, and locks for safes and

vaults, and so the American lock industry had its start. Each native craftsman

had his own ideas about security, and between 1774 and 1920, American lockmakers

patented some 3,000 varieties of lock devices. Among was the patent for a

"domestic lock," by Linus Yale, Sr. This lock was a modification of an

old Egyptian pin-tumbler principle that utilized a revolving cylinder.

In

the mid 1700s, locks were few in the Colonies and most were copies of European

mechanisms. With the founding of the Republic and the new prosperity, there was

a growing demand for sturdy door locks, padlocks, and locks for safes and

vaults, and so the American lock industry had its start. Each native craftsman

had his own ideas about security, and between 1774 and 1920, American lockmakers

patented some 3,000 varieties of lock devices. Among was the patent for a

"domestic lock," by Linus Yale, Sr. This lock was a modification of an

old Egyptian pin-tumbler principle that utilized a revolving cylinder.

During

the Middle Ages, locks and keys were highly ornate. Iron began to be worked

cold. It was no longer necessary for the smith to work quickly at the forge; he

now used a file, a cold chisel, and a saw with extraordinary dexterity. The

master locksmith designed special locks for cathedrals and churches in the shape

of a cross and embellished them with elaborate decorations. He acquired expert

skills in repoussť , ornametations, overlays, embossing, chaffing, piercing,

and created delicate fretwork in the popular scroll and leaf patterns of the

period.

During

the Middle Ages, locks and keys were highly ornate. Iron began to be worked

cold. It was no longer necessary for the smith to work quickly at the forge; he

now used a file, a cold chisel, and a saw with extraordinary dexterity. The

master locksmith designed special locks for cathedrals and churches in the shape

of a cross and embellished them with elaborate decorations. He acquired expert

skills in repoussť , ornametations, overlays, embossing, chaffing, piercing,

and created delicate fretwork in the popular scroll and leaf patterns of the

period. For

many centuries, keys represented authority, security, and power. Gods,

goddesses, and saints are described as holders of the keys to the Kingdom of

Heaven, to Bottomless Pit, to Gates of Earth and Sea. Kings, emperors, nobles of

the court, and cities and towns incorporated the symbol of the key into banners,

coats of arms and official seals. The delivery of keys to a castle, fortress, or

city was a ceremonial event, as is the presentation of the Key-To-The-City today

to a visiting dignitary.

For

many centuries, keys represented authority, security, and power. Gods,

goddesses, and saints are described as holders of the keys to the Kingdom of

Heaven, to Bottomless Pit, to Gates of Earth and Sea. Kings, emperors, nobles of

the court, and cities and towns incorporated the symbol of the key into banners,

coats of arms and official seals. The delivery of keys to a castle, fortress, or

city was a ceremonial event, as is the presentation of the Key-To-The-City today

to a visiting dignitary.

If

you have visited the Tower of London, you will remember the warder, dressed in a

red tunic and wearing a Tudor hat and ruff. Familiarly, he is called a

Beefeater. Specifically, he is an Honorary Yeoman of the Guards, a member of the

Queen's bodyguard. If you spoke to him, you may have heard the story of the

Ceremony of the Keys. Every night, the Chief Warder locks the Tower gates and

brings the keys to headquarters in the ancient fortress. The sentry calls out

"Halt! Who comes there?" "The Keys." "Whose

keys?" "Queen Elizabeth's keys." Everyone presents arms

and the warder calls out, "God preserve Queen Elizabeth." The guard

responds, "Amen." Tonight and every night, this traditional ceremony

of Britain continues. The yeoman repeats the same words that have never been

changed in 450 years.

If

you have visited the Tower of London, you will remember the warder, dressed in a

red tunic and wearing a Tudor hat and ruff. Familiarly, he is called a

Beefeater. Specifically, he is an Honorary Yeoman of the Guards, a member of the

Queen's bodyguard. If you spoke to him, you may have heard the story of the

Ceremony of the Keys. Every night, the Chief Warder locks the Tower gates and

brings the keys to headquarters in the ancient fortress. The sentry calls out

"Halt! Who comes there?" "The Keys." "Whose

keys?" "Queen Elizabeth's keys." Everyone presents arms

and the warder calls out, "God preserve Queen Elizabeth." The guard

responds, "Amen." Tonight and every night, this traditional ceremony

of Britain continues. The yeoman repeats the same words that have never been

changed in 450 years.